Donegal is a large county located in the north-western fringe of the Isle of Ireland. It is isolated from the rest of the Republic of Ireland – to which it belongs – by a very long border with Northern Ireland, except for a very narrow strip of land in its southern part. However, the border has become invisible since the Good Friday agreements of 1998, which put an end to the Troubles in Northern Ireland. Donegal is a rural and sparsely populated county despite undeniable touristic assets whose economic vitality largely depends on trade with Northern Ireland. The prospect of the return of a hard border following Brexit has for the moment faded away with the displacement of the border in the Irish Sea. However, this is only a temporary provision which does not prevent its return in the long term. This would be a major obstacle to the economic development of the county and its inhabitants’ daily life, a sword of Damocles testifying to the geopolitical and geo-economic issues at stake in the British Isles because of Brexit and to the status of the borders between member states and external states.

Image information

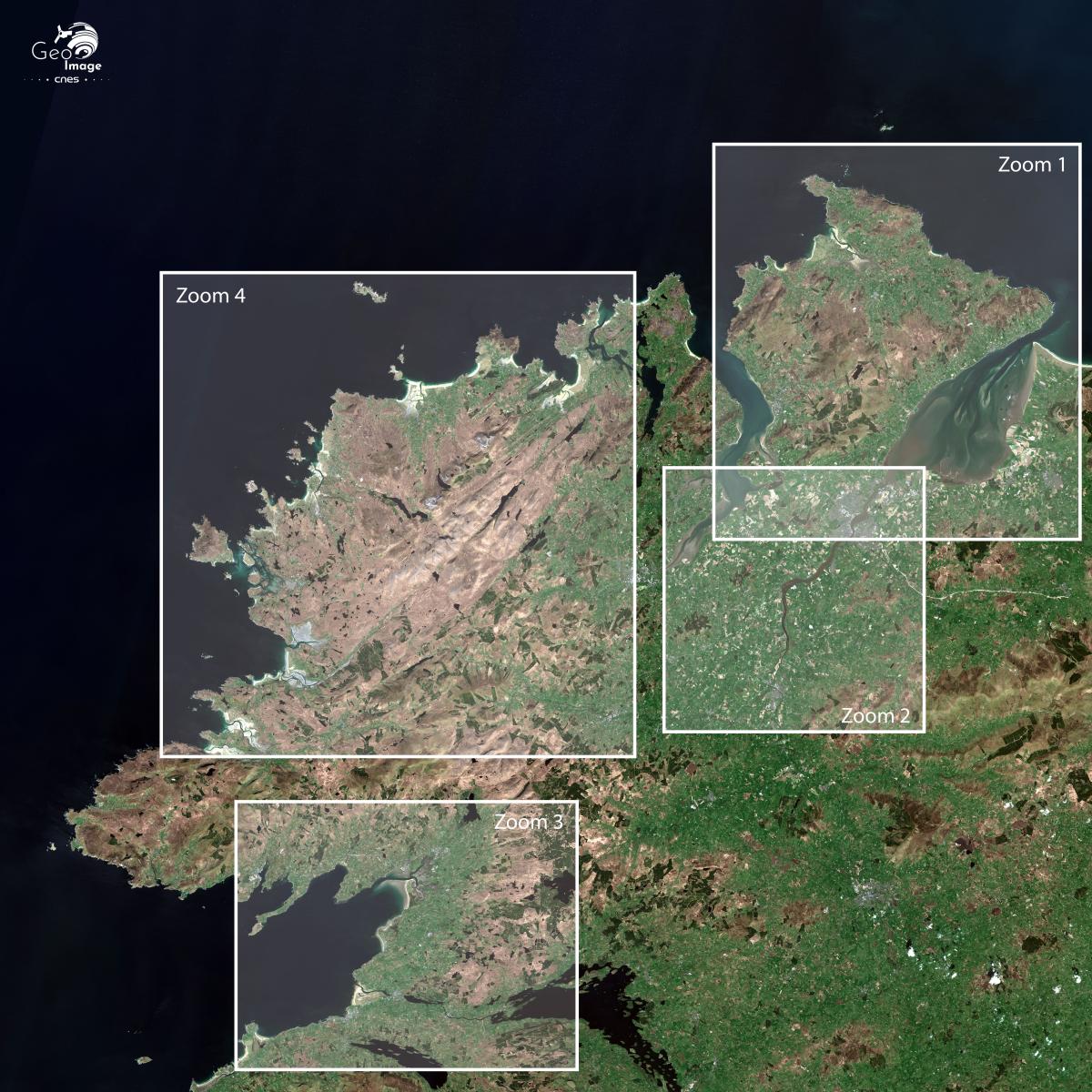

This image was taken on april 20, 2020 by the Sentinel 2B satellite. It is a natural colour image with native resolution at 10m.

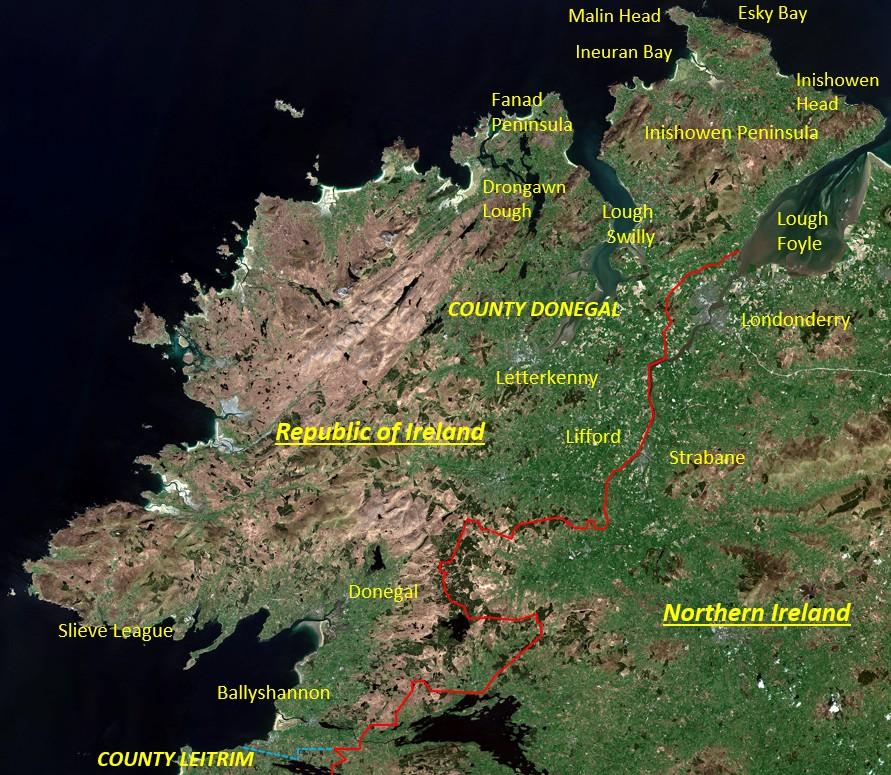

The image on the right shows some geographical landmarks.

General image without geographical landmarks

Contains information © COPERNICUS SENTINEL 2019, all rights reserved.

General presentation of the image

Republic of Ireland / Northern Ireland: a traumatic border turned peaceful, facing now the new post-Brexit uncertainties

The North West of the Island of Ireland: an Atlantic, rural and depopulated fringe

This satellite image shows the north-western tip of the island of Ireland, a western peninsula in Europe, where the seas and the lands are deeply intertwined. In the north, we can clearly see the very large and almost triangular Inishowen peninsula. In the west, it is bordered by 30km-long Lough Swilly, a vast and very deep estuary which grows narrower and narrower and in the extremity of which lies the town of Letterkenny. In the east, the peninsula is bordered by another large bay whose shape is almost oval. It is called Lough Foyle and is separated from the sea by a narrow stretch of water dominated by Inishowen Head. Londonderry, through which runs the River Foyle, lies in a large estuary in the extremity of this vast bay. Letterkenny and Londonderry are both located in natural shelters. The two cities are thus protected from the winds and currents of the Atlantic Ocean. To the west of Lough Swilly lies the Fanad Peninsula, separated from the rest of Donegal by the very narrow Drongawn Lough. The whole of the western part of Donegal is long coast hemmed with an alternation of jagged cliffs and small sandy bays. They are the first obstacles that the great Atlantic depressions encounter on their way eastward.

We can immediately see that the North West of the island of Ireland is above all an extremely rural area, and is potentially quite inhospitable in certain places. The image highlights a clear West/ East opposition. The coastal or inland highlands in the western part of Donegal appear in brown. They are quite low and covered in heaths. The eastern part of the county is lower and better sheltered. It is also more welcoming as evidenced by its agricultural organisation with its clearly identifiable cultivated farmland. All the usable agricultural areas are effectively farmed. Only the rocky barren lands of the Inishowen and Fanad peninsulas and the mountainous areas of western Donegal are not cultivated. Everywhere else, in the Foyle Valley and its tributaries, as well as in the northern ends of the two main peninsulas, we can identify an agricultural productive system composed of a myriad of cultivated farmland devoted to livestock.

Donegal is a sparsely populated county, with a population of only 159,200 inhabitants and a density of approximately 33 inhabitants per sq. km. It is very rural, as only 28% of the county’s population live in urban areas. The clusters of population are mainly located in the northern and eastern parts of the county, as well as around Donegal Bay. Between 2006 and 2016, the population increased by 8%. It could be the result of a certain attractiveness leading to the return to the countryside of urban dwellers attracted by the quality of life in the Irish countryside - when they can find a job there. 57% of the county’s population are active, 7% work in the agricultural sector and 9% work in the industrial sector. The services therefore employ the bulk of the county's labour force.

The border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland: a clear denominational and geopolitical divide

Although there are no obvious signs of it, this part of the island is divided and structured by a long border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. This boundary is obviously multidimensional: it is a State border, as well as the boundary of a monetary union for example, but it is, above all, a denominational and geopolitical divide.

As we can see in the image, the border has disrupted the urban network and the regional urban hierarchy. The Inishowen Peninsula is located in Donegal in the Republic of Ireland while Londonderry and Strabane, the small town situated upstream of the Foyle in the south of Londonderry, are two British cities since they are located in Northern Ireland, one of the four nations forming the United Kingdom. Letterkenny is situated in the Republic of Ireland, even though it is only 30 km away from Londonderry. Although Londonderry is a medium-sized city with 110,000 inhabitants, it is by far the largest city in the region. As for Letterkenny and Strabane, they are small cities, with respectively 19,000 and 13,000 inhabitants (in agglomerations comprising 42,000 and 40,300 inhabitants).

This border between Northern Ireland and Republic of Ireland was established on a relatively uniform natural environment. It is above all a geopolitical creation, in the sense given to the word by Yves Lacoste, which defines the rivalries of powers on a territory. It was created by London and it was a complete act of gerrymandering – the carving-up of boundaries for political purposes - based on the denominational geography of the island.

The point was to create a territory from scratch - Northern Ireland - where Unionism could keep political and economic control thanks to the presence of a predominantly Protestant population. Until the partition of Ireland in 1921, Donegal belonged to Ulster, one of the four historic Irish provinces - with Connacht, Leinster and Munster - and was one of the 32 Irish counties. After the partition, the largely Catholic County Donegal, was attached to Southern Ireland while the neighbouring counties of Foyle and Londonderry, where there was a Protestant majority, were among the six counties of Ulster which formed Northern Ireland.

This border is the direct consequence of two historical legacies dating back to two very different periods. The more recent one is the Irish War of Independence waged by the Irish Republicans against the British government. The older one dates back to the process of “Plantation of Ulster” - or colonisation - decided by the English monarch James I, who was also James VI of Scotland and at the same time King of Ireland - planned three centuries earlier, between 1608 and 1610, and effectively implemented from 1610 on.

A border born from a long war of anti-colonial independence in the 20th century

This war broke out on January 21, 1919 when members of the Irish Volunteers killed two members of the Royal Irish Mounted Police in an ambush near the town of Tipperary. On the same day, the first Dáil - an assembly of 27 Members of Parliament from the Republican political party Sinn Féin who were elected in the 1918 general election but refused to sit in the House of Commons - issued a declaration of independence and proclaimed the Republic of Ireland.

A guerrilla war was then waged by Irish republican forces against the British army, which led to the Government of Ireland Act, adopted on December 23, 1920. It divided Ireland into two autonomous territories, Southern Ireland and Northern Ireland. Southern Ireland was composed of 26 of the 32 Irish counties, with the exception of Antrim, Armagh, Down, Fermanagh, Londonderry and Tyrone as well as the urban districts of Belfast and Londonderry which formed Northern Ireland. Northern Ireland was therefore arbitrarily devised by London to bring together six of the nine counties of the traditional province of Ulster - excluding Donegal, Cavan and Monaghan - in which Unionists - Protestants loyal to the British Crown - had a clear majority.

The war of independence went on until a truce was declared on July 11, 1921. Negotiations led to the Anglo-Irish treaty, signed in London on December 6, 1921 and ratified by the Second Dáil in January 1922. On December 6, 1922, the entire island of Ireland became a Dominion of the British Empire, called the Irish Free State, sharing the same monarch with the United Kingdom and the other Dominions of the British Commonwealth.

Under the Constitution of the Irish Free State, the Parliament of Northern Ireland, opened by King George V on June 22, 1921 at Belfast City Hall, had the possibility to opt out of the Irish Free State within a month of its creation and subsequently join the UK. It took the Parliament of Northern Ireland only two days to make this decision. On December 8, 1922, Northern Ireland withdrew from the Irish Free State, whose territory then became the territory of Southern Ireland that had been defined by the 1920 Government of Ireland Act. However, the Irish Free State remained under British rule until 1937, when its constitution was replaced by the Irish Constitution declaring Ireland a democratic and independent state. Ireland officially became a republic in 1949.

From the making of a border in the 1920s to the return of old forgotten ghosts during Brexit in 2020

The current border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland therefore dates back to the 1920 Government of Ireland Act. It was initially devised as a provisional border. It became an international border on December 8, 1922 when the Parliament of Northern Ireland decided to exercise its right to opt out of the Irish Free State. In this context, the 1920 Act provided for the creation of a commission to determine the precise geographical delineation of the border, should Northern Ireland choose to opt out of the Irish Free State.

The commission - whose work was very controversial and whose report was not made public until 1969 - was installed in 1924. It met in 1925 and confirmed the delineation of the existing border at the end of 1925. The final agreement between the three parties - the Irish Free State, Northern Ireland and the United Kingdom - was signed on December 3, 1925 and then ratified by their respective parliaments. Therefore, the border remained provisional for five years, from the end of 1920 to the end of 1925. The agreement was then officially registered by the League of Nations on February 8, 1926.

The commission confirmed a border whose delineation had been anticipated as soon as 1914 by the British government. Three schemes were then prepared by senior Irish officials. It was Sir James B. Dougherty’s scheme which was finally selected. For administrative reasons - it seemed indeed more convenient not to get rid of existing administrative boundaries - he proposed that the border should follow the pre-existing boundaries of the counties.

It appears that the pre-existing administrative map, from which the border was confirmed, is based partly on natural boundaries and partly on the edges of the areas of influence of towns and cities such as Londonderry, Ballyshannon and Strabane. These boundaries are not always consistent with the region’s topographic and hydrographic characteristics as they cut through valleys for example or they do not follow natural obstacles. They sometimes follow the natural courses of waterways, then move away from them for no obvious reason, except perhaps for very local and specific land issues.

The case of Londonderry is particularly enlightening. Logically, the border follows the course of the Foyle, but turns away from it to bypass Londonderry, instead of cutting through the city. Consequently, Londonderry lies in Northern Ireland. But it is interesting to note that the initial proposals of the three senior Irish officials did not include Londonderry in Northern Ireland, due to its predominantly Catholic population. How to explain a choice which later had such dramatic consequences? As a matter of fact, Londonderry was an emblematic place of the English Plantations on the western domestic colonisation front as well as the stronghold of an influential Protestant minority that controlled political and economic levers. It was therefore politically unacceptable to make it the regional capital of a Catholic county in a Catholic state.

The border does not respect the region’s human characteristics either, since it crosses many roads and cuts through farms and even villages, thus multiplying absurd situations, which were highlighted during the debates on its possible return during the period of Brexit negotiations. As a matter of fact, in the region, Brexit has brought back some old ghosts that seemed to have long gone.

Brexit: from union to break-up, a new complex issue

This living border is a political, economic, social and geopolitical issue at local, regional (Ireland / Northern Ireland / United Kingdom) and international (European Union/ United Kingdom) levels. It has alternated phases of appeasement, intense tensions and crises. Between 1968 and 1998, during the thirty years of conflict in Northern Ireland called the "Troubles" which caused more than 3,600 deaths, the border was almost completely closed and guarded by the British army’s watchtowers. Then the Good Friday agreement of 1998 put an end to the Troubles. The Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom’s joint membership of the EEC and then European Union since 1973 has eased tensions and made the border completely invisible, enabling the free movement of people and goods, economic integration, etc.

However, Brexit has deteriorated the situation and revived the prospects of conflicts and tensions, which have unmistakably turned into major political crises. The divorce between the United Kingdom and the European Union undoubtedly darkens the future once more. The Irish border has been such a thorny issue in the United Kingdom and in the negotiations with the European Union that it prevented the divorce between the two parties for long. The border is 500 km long and has more than 200 crossing points – one every 2.5 km on average. It is also the only land border between the United Kingdom and the European Union. Its other peculiarity is that it has become almost invisible and that the Good Friday Agreement formally prohibits the return of a physical border, with customs posts and checks.

The British parliamentary elections of December 12, 2019 comfortably installed Boris Johnson as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. After Theresa May's repeated failures to get Westminster to accept the exit deal she had negotiated with the European Union in November 2018, Boris Johnson's victory confirmed the electorate’s approval of the exit deal he had successfully renegotiated in October 2019. The renegotiation mainly dealt with the Irish border, which will become an external border to the European Union, while having a very special status. The backstop option negotiated by Mrs May, which would have prevented the return of the Irish border, should the free trade negotiations between the United Kingdom and the European Union have failed, is long gone.

The new agreement between the European Union and the United Kingdom: a true high-wire act

The agreement negotiated by Boris Johnson with the European Union is a true high-wire act. It seeks to solve a major contradiction: how to protect the European single market of the United Kingdom without reinstating the border between Ireland and Northern Ireland? How to combine the impossibility of reinstating a border with the need to control the flow of goods and people following the exit of the United Kingdom from the European Union? Handling effectively this contradiction requires the implementation of a specific customs status for Northern Ireland.

Northern Ireland will indeed keep a foothold in the European Union. Although it is leaving the European customs union like the rest of the United Kingdom, it will have to comply with the rules of the European single market for the movement of goods, including VAT. Northern Ireland is considered as an entry point into the European customs union. The critical answer is the creation of a special status according to the final destination of goods. One the one hand, if they come from the United Kingdom and are to remain in Northern Ireland, they will not be applied tariffs, since Northern Ireland belongs to the same customs union as the United Kingdom. On the other hand, if they are only passing through Northern Ireland on their way to the Republic of Ireland or any other European Union member state, the British authorities will have to apply European tariffs. VAT will remain the same on the whole island to prevent trafficking. British customs authorities will be responsible for collecting customs taxes, under the supervision of a British and European joint committee.

Northern Ireland will therefore remain aligned with European Union regulations, at least four more years from the end of the transition period starting on 31 December 2020. There will not be any checks on goods at the crossing points of this invisible border – which will therefore remain so. Checks will take place at points of entry into Northern Ireland, i.e. ports and airports – in particular Belfast and Londonderry. In practice, the border is displaced into the Irish Sea.

This raises the question of the confirmation and sustainability of such an arrangement. Every four years, the Northern Ireland assembly will have to vote whether or not to continue with these provisions. This will undoubtedly cause significant political, and perhaps social, tensions. No doubt that there are – and will be – major differences on this subject in Northern Ireland between Republicans – who are in favour to the reunification of the island – and Unionists – who are still strongly attached to the British crown. The return of intercommunity violence, which is a mirror of political instability and tensions in Northern Ireland, is a possibility that should never be completely discarded in post-conflict Northern Irish society.

Detailed images

The Inishowen Peninsula

Image with geographical landmarks

Malin Head, the northernmost tip of the island

The northernmost tip of the island of Ireland is on the Inishowen Peninsula, which belongs to Donegal. It is located between Ineuran Bay and Esky Bay and it is of particular geological and morphological interest. It is home to Ireland's oldest and best-preserved glacial coasts, as well as the highest sand dunes in Europe. Malin Head’s steep cliffs and numerous coves make it a protected and inaccessible area, and a nesting site for many bird species.

Malin Head is also home to one of the most important weather stations in Ireland, established in 1870. In 1905 a transmission tower/ signalling post was built in Malin Head, called Banba Tower and named after the mythological Celtic goddess Banba, patron saint of Ireland, to establish communications between Europe and America. The tower is also an essential element for maritime navigation, which is particularly difficult and dangerous in the north of Ireland. Because of its geographic location, it played an essential strategic role, in particular during the Second World War.

A specific agricultural and rural system

The image shows the clear opposition between the cold and humid highlands covered in moors, clearly identifiable in brown, of the central zone and the peripheral countryside dominated by meadows and grasslands. The agricultural kaleidoscope that we can observe reflects the small or very small size of farms that is the direct consequence of the fragmentation of land ownership. This marginal and not very intensive agriculture is devoted to livestock. It is characterised by a very scattered rural habitat, connected by a network of narrow secondary roads. Clearly, this north-western area of the island of Ireland suffers from significant isolation, despite the relative proximity of Londonderry. The population of Inishowen is 40,500 and Buncrana, the most populous city on the peninsula, has only 3,400 residents.

Agriculture, fishing and aquaculture on the one hand, the food industry on the other hand are the dominant economic sectors in Donegal. With an average size of 27 ha., the 9,200 farms - compared to 29,000 in 1915 - are largely oriented towards traditional crops (potatoes, cereals including barley) and cattle, in particular sheep (20% of the Irish livestock). The food industry and its associated services (suppliers, transport, auctions, accounting, legal advice, etc.) account for 1,500 jobs in the county and 8,200 in the neighbouring counties. Tourism is the other important economic sector in Donegal and allows for economic diversification.

The plain of the Foyle: a border area between Ireland and Northern Ireland

Image with geographical landmarks

A well-developed agricultural system

This image shows the plain of the Foyle. As on the Inishowen Peninsula, we can observe a highly fragmented agricultural system and land ownership on both sides of the border. We can see very well that there are very few forests. Almost all the useful agricultural land is farmed. This agricultural network results in a very large scattering of dwellings, which are connected by a network of narrow secondary roads.

The Irish border begins in the extremity of the Foyle estuary, 4 km north of Londonderry. Then, it bypasses the city from the west and joins the Foyle about 5 km south of the city. Then, it follows the course of the Foyle until it reaches Strabane. On this section of the border, the river acts as a real natural boundary since there is no bridge over the Foyle between Craigavon Bridge in Londonderry and Lifford Bridge which connects Strabane to Lifford, in the Republic of Ireland.

Strabane and Lifford, border cities and the burden of the socio-economic legacies of the Troubles

In the centre of the plain, the region is structured by the presence of two cities which are very closely implanted on each side of the border. They epitomise regional inequalities and border effects. The town of Strabane lies at the confluence of the River Foyle’s tributaries – the Rivers Finn and Morne. The border line then leaves the course of the River Foyle for that of the River Finn southwards. Opposite Strabane, which is therefore located in Northern Ireland, on the other side of the river, lies Lifford, which is the administrative capital of Donegal despite its small size (1,600 inhabitants). Strabane is 500 metres away from the border with Ireland. It was founded by Scottish - Protestant settlers in the early 17th century, a few years before the official start of the Plantation process in Ulster.

Its position as a border city made Strabane an ideal target for incursions by paramilitary groups of the Irish Republican Army - IRA, Irish Republican Army - in Northern Ireland. As a result, Strabane suffered enormously, humanly and economically, during the Troubles. During this period, numerous murders and bombings took place in Strabane. The unemployment rate was among the highest in Northern Ireland. Strabane was then one of the most disadvantaged cities in the United Kingdom. The long-term consequences of the Troubles are still visible in Strabane. The town has, along with Londonderry, the lowest activity rate (62%), the lowest employment rate (54%) and the highest proportion of unskilled workers (23%) in Northern Ireland.

Ballyshannon, an umbilical cord at the border between Irish counties and at the border between Ireland and Northern Ireland

Image with geographical landmarks

The border issue is crucial for Donegal. Historically Donegal was bordering the Northern Irish counties of Derry, Tyrone and Fermanagh. Since the 2015 local government reform, Northern Ireland has been divided into eleven local authorities. Donegal borders Bordanagh and Omagh District Council and Derry City and Strabane District Council.

As the picture shows, Donegal is only attached to the rest of Ireland by a small corridor that is 9 km wide at the border with County Leitrim, 4 km south of the small town of Ballyshannon (2,300 hab.). To be even more precise, at the narrowest point, a kilometre further north, the distance between the coast and the border with Northern Ireland is only 7 km. But it is Ballyshannon’s bottleneck that perfectly epitomises Donegal’s isolation from the rest of the Republic of Ireland. Ballyshannon is located in the Erne Valley, and the River Erne runs through the city. The city expanded in a narrow passage less than two kilometres wide between the sandy estuary on the one hand and the River Erne and Assaroe Lake on the other hand. Both form a real natural border.

Many cross-border initiatives, funded by the European Union, have improved relations between border counties since 1998. The possible return of a border is therefore obviously a dreaded prospect and a major issue for the county, both for its inhabitants’ daily trips and for its economic vitality. The return of a border would necessarily strengthen the feeling of isolation and remoteness of the people living in Donegal and would most likely have a negative impact on the county's economic activity. The Troubles in Northern Ireland, during which the border was effectively closed, largely contributed to making Donegal unattractive for economic development, which kept unemployment high.

North West Donegal, a very isolated fringe

Image with geographical landmarks

This image shows the morphology of the north-western part of Donegal which belongs to the range of western coastal mountains which surrounds the central Irish plain. This part of Donegal is therefore largely composed of low mountains - the highest point is Mount Errigal, at an altitude of 725m - and hilly and rocky moors, oriented south-west / north-east and dotted with a multitude of lakes of very variable sizes. The image suggests an alternation of gently sloping moors and deeper valleys, carved by the glaciers that once covered Donegal.

Donegal is one of the largest counties in Ireland. It has the longest coast in Ireland (1,134 km). On this extremely rugged coastline, there are long white sandy beaches, dunes and cliffs, especially around the Inishowen and Fanad peninsulas. The shadows suggest high cliffs. Ireland’s tallest ocean cliffs are to be found in Donegal at Slieve League in the south west of the county.

Once again, the fragmentation of the agricultural productive system shows that all the useful agricultural land is farmed. The hilly and rocky moors make the development of large farmland impossible. The dwellings located along the coast between Donegal Bay and the Fanad Peninsula appear to be very isolated from the rest of the country and from decision centres, including regional ones. There are no major lines of communication. For most of the people living in Donegal, with the exception of those who live around Donegal Bay, there is no alternative but to drive through Northern Ireland to get to Dublin quickly. Londonderry and Belfast, two cities in Northern Ireland, are the two easiest points of attraction in terms of international connections. This has been so since the border became invisible with the Good Friday agreements of 1998. For people living in Donegal, the main issue today is to know how long this will last.

Additional image

The northern part of the island of Ireland, with Belfast to the east

Further resources

Sur le site Géoimage du CNES

Fabien Jeannier : Irlande/Irlande du Nord : Londonderry et sa région, une frontière en mutations et en débat

Autres sources

Fabien Jeannier, « Le Brexit et la frontière irlandaise », Géoconfluence, 2019,

Thibaut Harrois, « Brexit : l’enjeu nord-irlandais », 2019.

Ophélie Siméon, « Le Brexit et les deux Irlandes », 2019.

La création de la frontière :

Brigitte Dumortier, « Partition et frontière : le cas irlandais », Hommes et Terres du Nord, n°2-3, 1994, p. 103-111,

Conor Mulvagh, « How was the Irish border drawn in the first place? », The Irish Times, 11 février 2019,

The Irish Times, « Brexit Borderlands »

James Wilson, « Why is the Irish border where it is? Northern Ireland wasn’t always destined to be a six-county state », Irish Central, 26 septembre 2019,

Donegal, County profile, The Western Development Commission

Contributor / Translator

Fabien Jeannier, professeur d’anglais, chercheur associé au laboratoire Identité culturelle, textes et théâtralité, Avignon Université