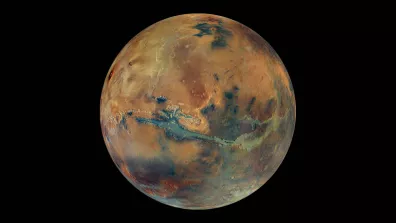

We all have a picture in our mind of Mars as a red, rocky, desert planet. But the “red planet” has many other surprising features that humans have been working to decipher with a series of spacecraft missions for more than 60 years.

Fast figures

| Distance from Sun | 227.9 million km |

| Volume | 1.632 × 1011 km3 (0.151 that of Earth’s) |

| Mass | 6.418 × 1023 kg (0.107 that of Earth’s) |

| Diameter | 6,794 km (almost half that of Earth’s) |

| Gravity | 38% that of Earth’s |

| Axial tilt | 25.2° |

| Revolution period | 687 Earth days |

| Rotation period | 24.7 hours |

| Temperature | –143°C to +20°C (–63°C on average at equator) |

| Known moons | 2 |

Small, red and surprising

Mars is one of the four telluric—terrestrial or rocky—planets in the solar system.

- Desert world?

Mars is a relatively small planet, seven times less voluminous and ten times less massive than Earth. We’ve also dubbed it the “red planet”, due to the iron oxide dust that coats the surface, giving it a rusty hue. It may appear a vast, arid desert, but appearances can be deceptive: the average temperature standing on Mars is –60°C. This is because it’s further from the Sun than Earth is (228 million kilometres away, versus 150 million kilometres for the Earth-Sun distance). The planet’s very tenuous atmosphere also means the Sun’s heat escapes easily.

- Mars’ structure in depth

Mars’ atmosphere is primarily composed of carbon dioxide (96%), with trace amounts of argon (1.93%) and nitrogen (1.89%). It’s 60 times less dense than Earth’s, which attenuates the planet’s greenhouse effect and therefore its ability to trap the Sun’s heat. But a few billion years ago, this atmosphere was much more like Earth’s. It has since been gradually stripped away as a result of the loss of its magnetic field and interaction with the solar wind of electrically charged particles. In comparison, our atmosphere here on Earth is shielded from the solar wind by the planet’s magnetic field.

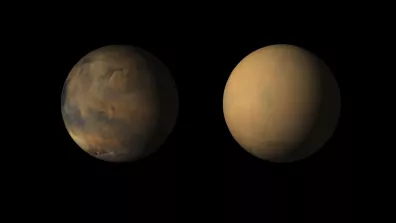

When a storm brews up on Mars, the atmosphere becomes thick with dust and the sky takes on a somewhat apocalyptic pink hue. These dust particles are easily blown into suspension because of the planet’s very weak gravity (38% that of Earth’s). They then remain in suspension as there’s no precipitation to remove them from the atmosphere.

- Largest volcanoes in the solar system

Mars has the highest elevations in the solar system. Most of these geological formations are “shield volcanoes”, so called because they’re shaped like flattened cones, resembling a shield lying on the ground. The widest is Alba Mons, spanning some 1,600 kilometres, further than the length of France! The highest peak is Olympus Mons, at 22 kilometres, nearly three times taller than Mount Everest.

- Distant cousin of Earth?

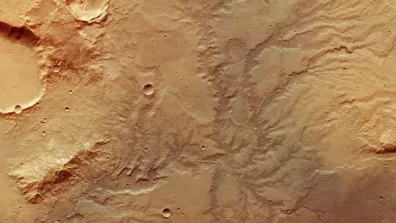

Earth and Mars have a few features in common. For example, water is found on both planets. However, we won’t be bathing anytime soon on Mars, as the water there is only present as water vapour or ice. Because of the atmospheric pressure and surface temperature, it’s impossible for water to persist in liquid form. But scientists have shown that billions of years ago, there were lakes, oceans, seas and rivers once flowing on the surface of the red planet.

The blue and red planets also have a similar axial tilt: 23.5° for Earth and 25.2° for Mars. A year on Mars thus has a spring, summer, autumn and winter like on Earth, only they vary in length and intensity in the two hemispheres: in the north, winters are short and mild, whereas in the south, they’re longer and colder. These differences are due to Mars being further from the Sun and to its egg-shaped orbit.

- Around Mars

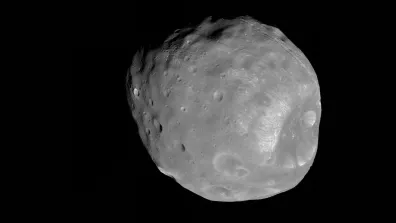

Mars has two small moons, Phobos and Deimos. Phobos is seven million times less massive than our Moon, and Deimos almost 50 million times less massive. Phobos orbits less than 6,000 kilometres from the planet, is oddly shaped and its surface is heavily cratered. In a few million years’ time, it will break up in Mars’ atmosphere and form a ring around the planet. Deimos is even smaller, orbiting 23,000 kilometres from Mars, and is as odd-looking as its big sister. The two moons take their names from Greek mythology, from the children of the goddess of beauty Aphrodite and the god of war Ares. Phobos means ‘fear’, and Deimos ‘terror’.

With their huge eyes, oversize head and green or grey skin, Martians—or little green men—have been made famous by science-fiction novels and movies. Less known is that they were inspired by a serious theory that gained credence.

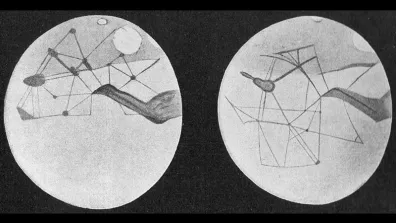

Towards the end of the 19th century, astronomers observed linear features on the surface of Mars. Some thought these were river networks or even irrigation canals dug by Martians to combat the dry conditions on their planet.

There was much speculation surrounding this theory in newspapers, including the Journal des Voyages in France, inspiring H. G. Wells’ 1898 science-fiction novel The War of the Worlds. The myth was finally debunked by the first space exploration missions to Mars, which showed there were no living beings on the red planet. Today, there are those who no longer believe in Martians but subscribe to another kind of science-fiction narrative: the transformation or “terraforming” of Mars to make it a new Eden for humankind.

Walking—well, almost—on Mars

Mars is the most explored planet in our solar system. What makes it such a prized destination is its relative proximity to Earth, at an average 62 million kilometres away (versus 591 million kilometres for Jupiter, for example).

- The star of space programmes

The exploration of Mars began less than 10 years after the first Sputnik satellite reached orbit in 1957, with the U.S. Mariner 4 spacecraft that completed a flyby of the red planet in 1965. As it approached, the probe confirmed there were no canals or living beings on the planet.

Today, 60 or so—mainly Soviet and American—spacecraft have approached Mars, some of them even landing on the surface. An increasing number of space agencies are sending space missions there. For example, the United Arab Emirates placed its Hope spacecraft into Mars orbit in 2021, taking the first-ever picture of the far side of the moon Deimos. Hope’s initial mission is to study weather patterns on Mars.

- Mars attacks…

Each successful mission to Mars is a major technological feat. With a success rate of less than 50%, there’s as much chance of failing as succeeding. Some missions have been complete failures, like Japan’s Nozomi orbiter, unable to reach the planet due to a serious electrical fault. Other projects have partly succeeded, like the European ExoMars mission to send the Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) and Schiaparelli lander, the latter unfortunately slamming into the surface. But TGO has been operational since 2016, and despite crashing into Mars, Schiaparelli sent back valuable technical data during its descent that notably enabled mission teams to establish the mishap was caused by a bug in the flight software.

- …And robots counter-attack!

In recent decades, we’ve pushed the boundaries of what we know about Mars. Whether observing it from afar or surveying its landscapes on the surface, exploration craft have gathered a wealth of data.

- Orbiters

There are seven active spacecraft currently orbiting Mars. The longest-serving are Mars Odyssey (NASA) and Mars Express (ESA), launched respectively in 2001 and 2003. Mars Express marked its 25,000th orbit in October 2023, although it was originally only expected to operate for a Martian year or sol, i.e. about two Earth years. As well as mapping and imaging regions of Mars, orbiters also serve as communication relays for rovers and landers on the surface, beaming back their data to Earth. For example, Mars Express provided a back-up relay for China’s Zhurong rover.

- Landers

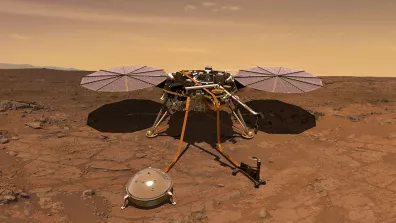

The first landers to set down—and survive—on Mars were Viking 1 and 2, in the late 1970s. They conducted the first in-situ analyses of the planet’s surface, whereas previously scientists only had meteorites to go on. In 2018, NASA’s InSight lander set down on Mars, carrying with it the SEIS seismometer developed by France to study the planet’s internal structure and seismic activity. However, such landers aren’t designed to rove about the surface like their wheeled counterparts.

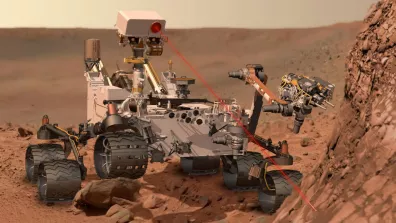

Mars rovers are trekking increasingly long distances. In 1997, Sojourner covered just 100 metres, whereas Opportunity clocked up 45 kilometres between 2004 and 2018. On these road trips, the rovers are mobile laboratories serving as the eyes, hands and legs of science teams. But their missions are not without risk: for example, the Curiosity rover sent to Mars in 2012 found itself experiencing electronic glitches due to solar radiation. Sharp rocks are also wearing down its wheels. But Curiosity is a tough customer: for more than 10 years now, this craft as heavy as a Renault Twingo has scouted the landscape to determine if the planet once supported conditions conducive to life. Its ChemCam scientific instrument designed in France gives it the ability to analyse the composition of Martian rocks.

1964: Mariner 4 (United States) - flyby

1969: Mariner 6 & 7 (United States) - flyby

1971: Mars 2 & 3 (USSR) - lander (failed) and orbiters

1971: Mariner 9 (United States) - orbiter

1976: Viking 1 & 2 (United States) - landers

1996: Mars Global Surveyor (United States) - orbiter

1997: Mars Pathfinder & Sojourner (United States) – lander and rover

2001: Mars Odyssey (United States) - orbiter

2003: Mars Express (European Union) - orbiter

2004: Spirit & Opportunity (United States) - rovers

2005: Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (United States) - orbiter

2005: Phoenix (United States) - lander

2012: Curiosity (United States) - rover

2014: Mars Orbiter Mission (India) - orbiter

2014: MAVEN (United States) - orbiter

2016: Trace Gas Orbiter (European Union/Russia) - orbiter

2018: InSight (United States) - lander

2018: MarCO (United States) – telecom relay cubesats

2021: Mars Hope (United Arab Emirates) - orbiter

2021: Tianwen-1 & Zhurong (China) - orbiter, lander and rover

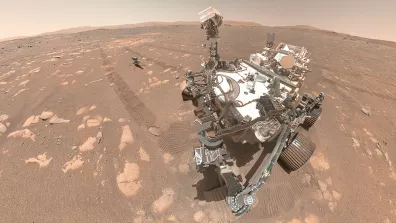

2021: Perseverance (United States) - rover

2024: Escapade (United States) - 2 microsatellite orbiters

2024: Mangalayaan 2 (India) - orbiter

2026: Mars Moons Exploration (Japan) – return of samples from Phobos

2028: Rosalind Franklin (European Union) - rover

2035-2045: Mars Sample Return (United States and European Union)

Mars rovers have thus enabled some great scientific discoveries. Set down on the surface in 2021, Perseverance has for example confirmed the presence of water 3.6 billion years ago in Jezero Crater. NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) plan to work together in the years ahead to bring back to Earth the samples collected by Perseverance via the Mars Sample Return (MSR) mission. A lander carrying a small ascent vehicle will retrieve the sample containers cached by Perseverance. The ascent vehicle carrying the precious samples of Martian dust will then rendezvous in orbit with a European spacecraft that will return them to Earth, probably in 2033.

The second leg of the European ExoMars mission is set to get underway in 2028, with the launch of Rosalind Franklin. This rover will be carrying a battery of scientific instruments to look for signs of ancient life on the red planet.

- Next step: crewed missions?

Humans on Mars: science-fiction or reality? Space agencies have been scratching their heads for decades as they contemplate sending crews of astronauts to Mars. After the Moon, it’s the next logical step in the human space adventure. But it won’t be a walk in the park, as such daunting missions come with a whole host of constraints.

When will we set foot on Mars?

The first challenge is the engineering one of building much larger rockets capable of lifting the tens of tonnes of supplies needed to survive on Mars: food, water and scientific equipment and instruments. Other constraints are more to do with the planet’s environment: cosmic radiation, storms and of course the absence of oxygen. Lastly, astronauts will have to contend with isolation and confinement, without recourse to direct assistance from Earth. There’s a good chance that crews will flyby Mars in a few years or so; but landing and living on the red planet is a wholly different proposition…

Walking on Mars | Mars challenges

Quiz

Mars has the highest peaks in the solar system, among them Olympus Mons, reaching 22,000 metres. Why do you think its volcanoes are so tall?