Between September and October, the Airbus A310 Zero G aircraft operated by CNES subsidiary Novespace completed a series of sorties over the Bay of Biscay for its 69th parabolic flight campaign, carrying an international crew of scientists doing research in near-weightless conditions. Among them was a team from the Mohammed Bin Rashid University of Medicine and Health Sciences (MBRU) in Dubai. Their goal was to understand how switching between microgravity and hypergravity affects the way our heart and postural system interact.

This unprecedented medical experiment was supported by CNES’s CADMOS centre for the development of microgravity applications and space operations.

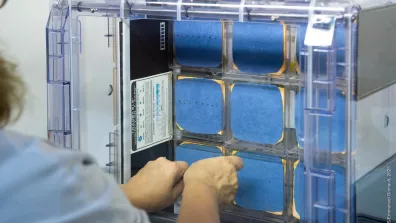

Located in Toulouse, CADMOS is a key cog in the French space value chain. Straddling research, industry and space operations, it helps to turn science and technology ideas into experiments in microgravity conditions. It conceives, prepares and monitors experiments conducted during parabolic flight campaigns or aboard the International Space Station (ISS).

CADMOS applies the directives from CNES’s international relations team and its partnerships with other agencies. We’re like a team leader, working with researchers to ensure their experiments are tailored to the safety constraints of parabolic flights.

- CNES parabolic flights project leader

A shining example of European cooperation

European parabolic flights are today a model of scientific cooperation built on a close partnership between CNES, ESA (European Space Agency) and DLR (the German space agency). “It’s a collaboration that works extremely well,” underlines Sébastien Rouquette. “A test platform shared in true team spirit.” Each partner is responsible for about one-third of the activity, striking a good balance to guarantee the programme’s long-term future. It’s also a model like no other, as in other countries parabolic flights are regularly entrusted to private operators or remain the preserve of space tourism.

Science as a common language

Historically, CNES has built strong partnerships with Russia for human spaceflight and with the United States in material sciences. These partnerships, in some cases going back several decades, have now been terminated due to the political context. But despite this, there is still good momentum globally. The United Arab Emirates, through their partner university, are one of the emerging players looking to do research in microgravity. Discussions are also underway with India, which is showing increasing interest in parabolic flights for science.

These new partnerships illustrate the global dimension of space research, where microgravity is becoming a shared field of experimentation to gain fresh insights into human physiology, material physics or fluid behaviour. And while parabolic flight campaigns provide a quick way to test out new ideas, the most promising experiments are subsequently adapted for long sojourns in space.

CADMOS’s role is to serve as a gateway between research here on Earth and aboard the ISS. Its expertise is proving all the more vital now that crewed spaceflights and in-orbit research are attracting renewed interest with new challenges ahead like lunar missions and private space stations, for example. For Sophie Adenot’s Epsilon mission, the Toulouse-based centre is preparing and will be tracking several life sciences and human physiology experiments, demonstrating once again its expertise in real-time operations management and scientific monitoring. But contrary to what you might think, in-orbit experiments coordinated by CADMOS are not only done by French astronauts: all of the ISS crew may be called on to deploy devices designed in Toulouse.

Despite the distances, borders and current turmoil in the world, microgravity research remains a window for dialogue and peaceful cooperation. Each flight, each shared experiment reminds us that science—be it in our skies or in space—is truly a terrain connecting nations.