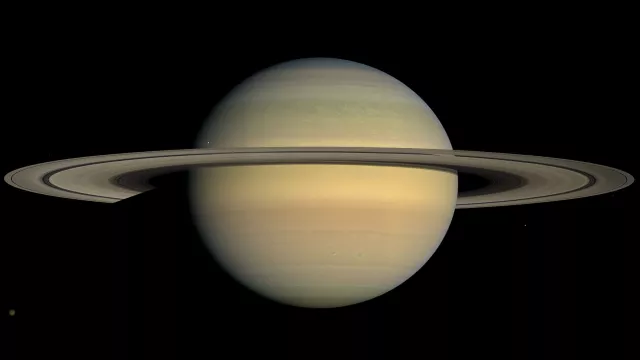

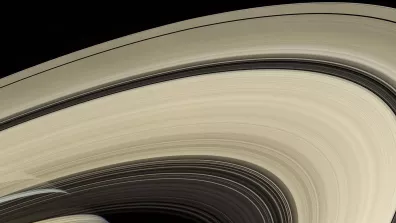

Saturn is immediately identifiable by its majestic rings. It’s not the only planet with rings, but they are unique in our solar system.

Fast figures

| Distance from Sun | 1.4 billion km |

| Volume | 8,271 3 × 1014 km3 (763 Earths) |

| Mass | 5,684 6 × 1026 kg (95 Earths) |

| Diameter | 116,460 km (9 times that of Earth’s) |

| Gravity | 106% that of Earth's |

| Axial tilt | 26.7° |

| Revolution period | 29.4 Earth years |

| Rotation period | 10 hrs. 33 min. |

| Temperature | –190°C at top of clouds |

| Known moons | 145 |

A giant ball of gas

Saturn is the sixth planet from the Sun, at a distance of 1.4 billion kilometres, and the second largest in the solar system after Jupiter. Its size and composition make it what’s termed a “gas giant”. Gas because that’s what Saturn is made of—mostly hydrogen and helium—and giant because you could fit 770 Earths inside it. It has no solid surface and the lowest density of all of the solar system’s planets, eight times less dense than Earth. It’s much more voluminous than massive or heavy—if there were a swimming pool large enough to hold it, it would float!

Let’s take a dive towards Saturn: first off, we go through the massive storms in its atmosphere, a thousand times more powerful than anything on Earth. Winds reach 1,800 km/h and some of these storms are so large they can be seen through a telescope from Earth. An example is the Great White Spot, a giant storm that occurs once every Saturnian year, or 29 Earth years. Such storms can span more than 15,000 kilometres—in comparison, the diameter of Earth is 12,800 kilometres—and spark dozens of lightning flashes per second.

Next up, we reach Saturn’s thick cloud layers, composed mainly of hydrogen, and helium. The deeper we go, the higher the pressure and temperature get. The gases are compressed so much that they become liquid. In this state, we call them metallic hydrogen and helium, because they take on the properties of metal. And at the centre of the planet is its solid core, an iron and nickel sphere twice the size of Earth, at a temperature of around 11,700°C.

Because of its 27-degree axial tilt, Saturn has seasons, each lasting seven years, much longer than on Earth because the planet takes 29 years to complete a full revolution of the Sun. Saturn spins around once in just 10 hours and 33 minutes. This rotation period is what gives it an oblate shape, bulging at the equator and flattened at the poles. So, contrary to what you might think, Saturn is not really round.

Saturn’s entourage

There’s nothing like Saturn’s rings anywhere else in our solar system. While all gas giants have their cortege of rings, Saturn’s are particularly striking as they are larger, more visible and mysterious.

Drawings or films often depict them like vinyl records revolving around the planet. However, they are neither solid nor continuous. They’re composed of billions of water ice grains ranging from micrometres to metres in size. Aggregated together, they form rings tens of metres thick in places—the width of a hair on the scale of Saturn—and all spin in the same direction and in the same equatorial plane.

The main rings extend 400,000 kilometres on either side of the planet. There are seven of them, named A to G in order of their discovery. Other even larger rings lie several million kilometres away, but they are harder to see, as they are more diffuse and contain fewer ice particles. There are gaps between the rings, termed divisions.

So why is Saturn the only planet with rings like this? Scientists believe they could be remnants of an asteroid or moon torn apart as it got too close to the planet, or they may have formed out of the original nebular material, a kind of soup that existed when the solar system was first formed.

- Saturn and its moons

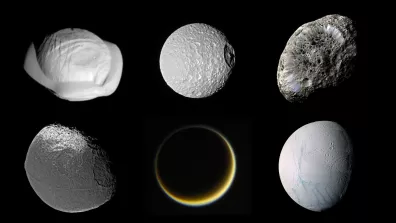

There aren’t just rings around Saturn, as they co-habit with some 150 moons of all shapes and sizes, some large, some small, some light, some dark, some bright and some riddled with craters. The most massive lie outside the rings, but others are embedded between them, in the divisions. The latter are called “shepherd moons”, as they stabilize and contain—or “herd”—the rings, deflecting their edges due to gravitational influence. Notable cases are the moons Pandora, Prometheus and Atlas.

But the most remarkable of all is without doubt Titan, which alone represents 96% of the mass—moons and rings—orbiting Saturn. Titan is the only moon in the solar system with a dense, nitrogen-rich atmosphere. Like Earth, whose seasons and climate are defined by the water cycle, Titan is characterized by methane cycles that shape its surface landscapes, notably lakes, a sea and rivers.

Another interesting moon is Enceladus, which could harbour the ingredients for life as we know it, i.e., organic matter, heat and liquid water. Astronomers have observed plumes venting from a vast ocean beneath the moon’s icy crust. The European Space Agency (ESA) in particular plans to send a mission to Enceladus around the 2050 timeframe.

Mimas is a surprising moon pockmarked with craters. One of these, Herschel, is 130 kilometres wide, a huge crater for a body with a radius of just 200 kilometres. The impact that formed this crater almost shattered Mimas altogether, so powerful that it left a trace on the opposite side of the globe. Its atypical appearance may remind you of a very famous spacecraft: the Dark Star in Star Wars!

Saturn here we come!

Visible from Earth, Saturn has been observed for centuries. But over the last 20 years, we’ve succeeded in surveying it up close.

- First observers

Saturn has been known to humans for a very long time, as it could be seen from Earth with the naked eye. The 17th-century astronomer Galileo was the first to observe it with a scientific instrument, an early version of the telescope. But he couldn’t see the rings clearly enough to understand what they were. As a result, they were initially depicted as giant ears on either side of the planet. It was physicist Christian Huygens who first postulated the rings’ existence in 1655, at the same time discovering the moon Titan. His colleague Giovanni Domenico Cassini determined that what was thought to be a single ring was in fact several rings with divisions between them, the largest of which was named after him.

- Unveiling Saturn’s secrets

The first mission dedicated exclusively to exploring Saturn was Cassini-Huygens, launched in 1997 by the U.S., European and Italian space agencies. During the course of their journey through the solar system, the Voyager 1 and 2 probes —launched in 1977—obtained pictures of Saturn as they flew past, but Cassini-Huygens had loftier ambitions.

The mission set down the Huygens lander on the surface of Titan and placed the Cassini spacecraft into orbit around Saturn to conduct a comprehensive study of its system. Huygens thus delivered new insights into the moon, its landscape, surface features and composition, while Cassini completed 293 orbits of Saturn, taking 450,000 pictures in the process. By the end of the mission in 2017, astronomers had discovered 10 new moons and were able to see the moon Phoebe in unprecedented detail, as well as plumes venting from Enceladus, and to determine the age of Saturn’s rings, estimated at 100 million years—a truly fantastic feat of science and engineering.

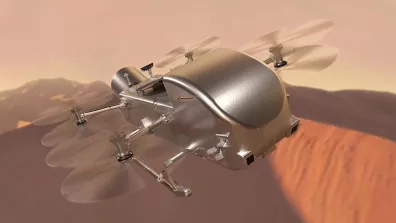

The next mission to Saturn is Dragonfly, which aims to send a drone to survey the surface of Titan. This 800-kilogram U.S. craft is no toy: it will seek out biosignatures, indicators of lifeforms that may have developed on the moon. France is contributing to the mission’s mass spectrometer. Dragonfly is scheduled to depart in 2028.

Quiz

The Cassini-Huygens mission, launched in 1997, is so far the most important mission ever to explore Saturn. It came to an end in 2017, having accomplished all of its science goals. But what became of the mission’s Cassini orbiter?