Neptune lies almost at the very edge of our solar system. It’s the eighth planet from the Sun, making it difficult to explore. So what secrets might this distant planet hold?

Fast figures

| Distance from Sun | 4.5 billion km |

| Volume | 6.253 × 1013 km3 (57.7 Earths) |

| Mass | 1.024 × 1026 kg (17 Earths) |

| Diameter | 49,528 km (3.9 times wider than Earth) |

| Gravity | 110% that of Earth’s |

| Axial tilt | 28.32° |

| Revolution period | 164.8 Earth years |

| Rotation period | 16 hrs. 6 min. |

| Temperature | –218°C at cloud tops |

| Known moons | 14 |

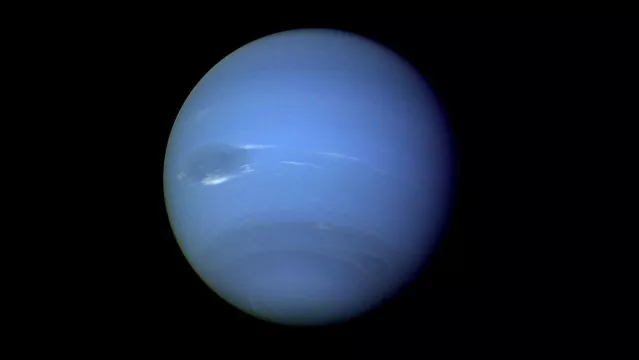

The ice giant

Neptune is the most distant planet in our solar system, lying 4.5 billion kilometres from the Sun, beyond Uranus. The two planets are so similar they could almost be mistaken for twins.

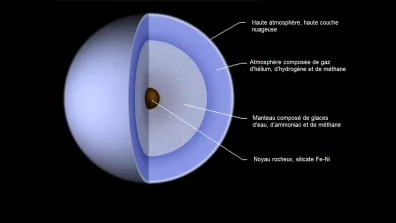

Neptune and Uranus are giant planets like Jupiter and Saturn, with an atmosphere of hydrogen and helium, and no solid surface. But Neptune—like Uranus—is also composed of icy materials, which is why we call them ice giants. However, we’re not talking about frozen water. Here, by “icy” materials we mean substances that turn into gas at low temperatures and may be solid, liquid or gaseous. For example, we find ammonia, water and methane on both planets, and it’s this methane that gives them their blue hue.

Neptune’s core and mantle are not gaseous. The core is made up of nickel, iron and silicates at a temperature approaching 8,000°C, hotter than the surface of the Sun. And the pressure is 8 million times higher than in Earth’s atmosphere. In these conditions, all icy materials melt into a sort of giant boiling bath of liquid ammonia and methane.

As we move upwards and away from the core, the temperature and pressure drop. In Neptune’s upper atmosphere, above the cloud tops, the thermometer can plummet as far as –220°C. Here, the most violent storms in the solar system rage, with winds of up to 2,100 km/h. In comparison, the most powerful winds on Earth don’t exceed 400 km/h. These storms can be seen from Earth, forming spots on the planet’s surface like the Great Dark Spot, a giant anticyclone the size of Earth.

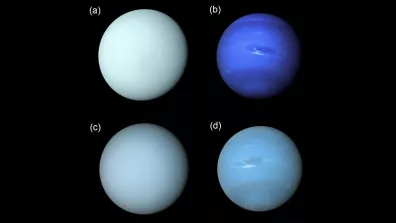

Contrary to what you may have seen, Neptune is not deep blue. This fact was revealed by research at the University of Oxford, published in January 2024. While the deep blue orb banded with white is certainly majestic, in reality the planet is a much lighter shade. The pictures taken in 1989 by Voyager 2 during its flyby were deceiving, because the science team in fact increased the contrast, making the colours appear deeper. In fact, it’s almost the same shade of greenish blue as its twin Uranus. It was notably using spectrometers—instruments that measure light wavelengths—that researchers found this out.

Around Neptune

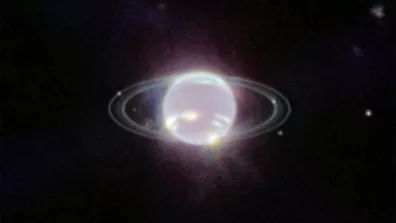

Like other giant planets, Neptune has a ring system (five rings).

- Rings

Neptune’s rings are dark and thin, making them difficult to observe. The outermost ring contains brighter regions called arcs. These arcs were named Courage, Liberté, Egalité 1, Egalité 2 and Fraternité (Courage, Liberty, Equality and Fraternity) by the French science team that identified the last three of them in 1986. We’re still not certain about their composition. They could contain ice particles covered in dust and silicates, or a substance composed of carbon (which would explain their reddish colour).

- Moons

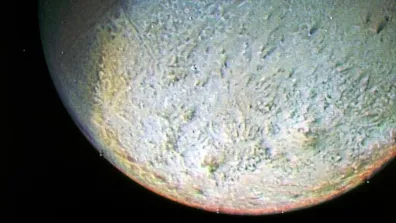

Neptune has 14 known natural satellites. Of these, Triton accounts for 99.5% of the total mass orbiting the planet (moons and rings). This moon intrigues astronomers because it’s the only large moon in the solar system with a retrograde orbit; in other words, it circles the planet in a direction opposite to Neptune’s rotation. Scientists can deduce from this feature how Triton formed, as a retrograde moon can’t have originated from its parent planet. Triton is thus thought to have been captured by Neptune from the Kuiper Belt, a region of asteroids on the outer edges of the solar system, beyond Neptune. The Kuiper Belt also contains dwarf planets like Pluto.

The unknown planet hidden from view

Neptune is the only planet in the solar system discovered by maths before its existence was confirmed by observations. As it can’t be seen with the naked eye, it was impossible to find it without a telescope.

- Discovered by maths

The story of its discovery begins with that of its twin, Uranus. In the 19th century, astronomers attempted to calculate Uranus’ orbital path, but their estimates were wrong and its observed position didn’t match their calculations, as if another unknown celestial body was perturbing its orbit… Scientists therefore hypothesized there could be an eighth planet hiding behind Uranus. Two astronomers set out to find it: John Couch Adams from Great Britain and Urbain Le Verrier from France. When the latter finally calculated the possible coordinates of the new body, he asked his friend Johann Gottfried Galle to survey this region of the sky with his telescope, and bingo! Galle observed Neptune for the first time in 1846.

But what about British astronomer Adams’ role in all this? He had indeed accurately calculated Neptune’s position to within two degrees, but the Director of the Cambridge Observatory tasked with looking for the planet didn’t find it, because his star maps were out of date. He had in fact observed it on two occasions but failed to recognize it as such. Urbain Le Verrier is therefore credited in the history books with discovering Neptune.

- Exploring Neptune

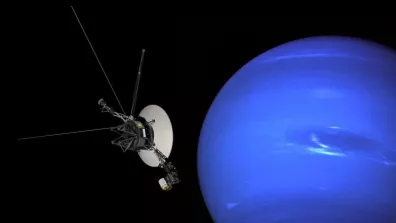

The U.S. Voyager 2 is the only spacecraft ever to have approached Neptune. Launched in 1977 to explore the solar system, the probe flew by the planet in 1989. Although only brief, this flyby enabled astronomers to discover Neptune’s rings, whose existence had never been proved. They also found six new moons. The data gleaned from this encounter constitute most of what we know about the planet.

Today, we have the capability to send spacecraft to Neptune, but in practice such a distant exploration mission, which would involve placing a spacecraft in orbit around the planet, is fraught with difficulties. The engineering and cost challenges would be huge. Neptune is therefore likely to remain one of the least known planets in the solar system for some time yet.

Quiz

With our current spacecraft, it would take about 12 years to get from Earth to Neptune. But if we imagine that we could travel at the speed of light, how long would it take to reach the solar system’s most distant planet?