“A weather forecast has two ingredients,” explains Nadia Fourrié, deputy director of CNRM, the national meteorological research centre. “The state of the atmosphere at a given time, characterized by winds, pressure, temperature and humidity; and software able to simulate, according to the laws of physics, how it’s likely to evolve from that point. This process is iterated at least every six hours.”

And to determine the state of the atmosphere, weather forecasters rely on reams of data from ground stations, aircraft, ocean buoys and satellites. “Half of the data used by our national weather service Meteo-France are from French IASI instruments flying on Europe’s two Metop satellites,” says Nadia. “These instruments give us direct readings of two crucial variables: atmospheric temperature and humidity. So it’s not hard to see why we’re eagerly awaiting IASI’s successor.”

The wait will come to an end this August when Ariane 6 launches Europe’s second-generation Metop-SG satellite, carrying IASI-NG (Infrared Atmospheric Sounding Interferometer-Second Generation), IASI’s successor. IASI-NG will observe the same atmospheric parameters and components, only better.

More reliable forecasts

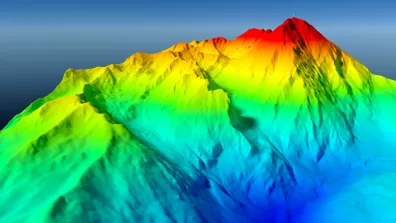

IASI and IASI-NG are infrared spectrometers that sense and record infrared waves emitted naturally by Earth’s surface, at wavelengths between 3.6 and 15.5 micrometres to be precise (see box). The data thus collected, called spectra, tell scientists about the environment the waves travelled through, i.e., the atmosphere: its gas composition (what species and in what amounts), humidity and temperature, at all altitudes.

Although they operate on the same principle, IASI and IASI-NG weren’t designed the same way. “We chose to go with different technologies,” explains François Bermudo, IASI-NG project leader at CNES. “To develop an instrument offering better performance in terms of radiometric noise and spectral resolution, which have both been increased twofold.”

What this means is that IASI-NG’s measurements will be two times “sharper”, as distortions due to the instrument will be better controlled, and two times more detailed: for the same observation in the thermal infrared, the new instrument will be capable of recording 16,900 “sub-divisions” of this interval, against 8,400 for IASI. “IASI-NG’s data will enable us to calculate an initial state of the atmosphere more accurately than ever before,” says Nadia Fourrié enthusiastically. “And that means more reliable forecasts!” For example, in the case of extreme weather events.

IASI-NG spectra will more precisely describe humidity fluxes in the first few kilometres above oceans, like the Atlantic, where depressions form. We’ll thus be able to better forecast storms, how they’re likely to evolve, their track and how much precipitation they’ll bring.

- Deputy Director of CNRM, the national meteorological research centre

Operational continuity and a longstanding partnership

IASI-NG is the result of more than 10 years of research and development efforts by CNES, the manufacturer Airbus Defence & Space and scientists. “The instrument was designed to meet their requirements,” says François Bermudo.

From the outset, we worked with a group of 20 scientists from research laboratories in the fields of air quality and climatology, with international weather services and of course our national weather service Meteo-France.

- IASI-NG project leader, CNES

“We ensured that Meteo-France’s forecasters would benefit from IASI-NG’s data as easily and as quickly as possible,” adds Adrien Deschamps, Atmosphere and Meteorology subject matter expert at CNES. “They use complex software ingesting very heterogeneous data and it’s not easy to input new types of data. So we did a lot work with them in the preliminary stages.”

This partnership initiated with the first IASI generation has made the instrument the gold standard for space-based infrared atmospheric sounding. And a large number of weather services use IASI data, like the European Centre for Medium-range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) and the UK Met Office.

A tale of spectra

IASI-NG generates spectra, in the form of curves, from the infrared radiation emitted by Earth. These spectra tell us about the atmospheric column the infrared waves passed through, interacting with gas molecules and fine dust particles they encounter, when they are either absorbed or re-emitted into space. This creates peaks and troughs in the spectra that we can attribute to a particular molecule, according to the wavelength. Specialists can then deduce which molecules—carbon dioxide, water vapour, ozone, sulphur dioxide, etc.—are present between the ground and the top of the atmosphere, at what altitude and in what quantity.

But how do we determine temperature or water vapour quantities (humidity) from a spectrum? Weather forecasters do this by comparing spectra, i.e. “field data”, with model simulations. These computing tools enable them, for a given concentration of water vapour and temperature, to simulate the infrared radiation at the top of the atmosphere. These parameters are then adjusted to match the simulation to observations.

European sovereignty

“Historically, the world’s national weather services have always worked together,” says Adrien Deschamps. “There are data sharing agreements between the European Union, the United States and Asian nations. But we’re not sure whether our U.S. counterparts are going to be able to share information freely, nor whether they’ll continue investing enough to maintain their own observation capabilities.”

“The geopolitical context is pushing us to strengthen Europe’s strategic independence, and weather satellites like Metop-SGA are a key component of that.”

- Atmosphere and Meteorology subject matter expert, CNES

The stakes of weather forecasting are indeed high, be it for mitigating dangerous events, storms or heatwaves, ensuring safety of transport, notably for air traffic, anticipating crop yields, managing solar and wind energy or supporting deployment of armed forces… not to mention Sunday family barbecues!

40 years of comparable data

Of the 54 essential climate variables (ECV), 16 relate to the atmosphere and all of these are observed or measured by IASI: surface temperature, greenhouse gas concentrations, presence and concentration of aerosols, etc.

“IASI has been measuring these parameters for nearly 20 years,” underlines Cyril Crevoisier, research director at the LMD dynamic meteorology laboratory, attached to the French national scientific research centre CNRS. “And that’s set to continue with the three IASI-NG instruments to be orbited in 2025, 2032 and 2039.” And to ensure data uniformity between the two generations of the instrument, CNES has planned to fly the Metop-C satellite carrying IASI in tandem with Metop-SG-A1, carrying the first IASI-NG instrument. “They’ll fly 30 seconds apart so that we can compare and inter-calibrate their data.” Continuity of measurements for climate science is thus assured through to 2045.